I was born in America; my parents fled the Soviet Union. When I was 11 years old we moved to Ukraine, where I lived, grew up, studied, and worked. I returned to the States in my early twenties, while my family continued residing in Ukraine.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, I knew I had to go back to help. I arrived in March and assisted with translation at the Romanian border, evacuating people from the East, where heavy bombing and Russian occupation had begun and was escalating. I participated in delivering humanitarian aid, supporting handicapped individuals, cleaning the aftermath of bombings, and visiting those who had lost everything.

Millions of people were forced to leave their homes and begin anew. Some endured challenging conditions, living in the metro for months. Others returned home to find it obliterated, now residing in tents, chicken coops, or undamaged sheds. Many still live abroad, awaiting the opportunity to return home.

I encountered individuals separated from their families, uncertain of their whereabouts, and those who witnessed the loss of family members. Friends dedicated their lives to protecting their people, country, and freedom by joining the fight.

The war touched every life profoundly and continues to do so. Despite the loss, despair, and destruction, there remains an unwavering belief that Ukraine will triumph, rebuild, and live in freedom.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, I knew I had to go back to help. I arrived in March and assisted with translation at the Romanian border, evacuating people from the East, where heavy bombing and Russian occupation had begun and was escalating. I participated in delivering humanitarian aid, supporting handicapped individuals, cleaning the aftermath of bombings, and visiting those who had lost everything.

Millions of people were forced to leave their homes and begin anew. Some endured challenging conditions, living in the metro for months. Others returned home to find it obliterated, now residing in tents, chicken coops, or undamaged sheds. Many still live abroad, awaiting the opportunity to return home.

I encountered individuals separated from their families, uncertain of their whereabouts, and those who witnessed the loss of family members. Friends dedicated their lives to protecting their people, country, and freedom by joining the fight.

The war touched every life profoundly and continues to do so. Despite the loss, despair, and destruction, there remains an unwavering belief that Ukraine will triumph, rebuild, and live in freedom.

Evacuating From Ukraine To Romania When The War Began

Oksana, resting in a blue tent at the border with her two daughters, Zorina and Polina. After a journey of over 24 hours from Kryvyi Rih, they are visibly exhausted. Her husband and older daughter remained behind to contribute to the war effort.

Ukrainians at the border in Romania find themselves waiting for hours to board a bus or train to their next destination. Their lives have been completely uprooted, changed, and now they face the reality of starting anew as refugees in a foreign country.

Katya, worried about her family remaining in Ukraine, insists, "I'm not a refugee," in an effort to preserve her dignity and humanity.

Teenagers anxiously checking the latest news from Ukraine first thing in the morning.

At 62 years old, Lida has eight children of her own and has adopted nine more, some with learning disabilities. She shared photos of her family and reminisced about life before the war. She crossed the Romanian border with her children, unsure of their next destination while her husband remained behind to help end the war.

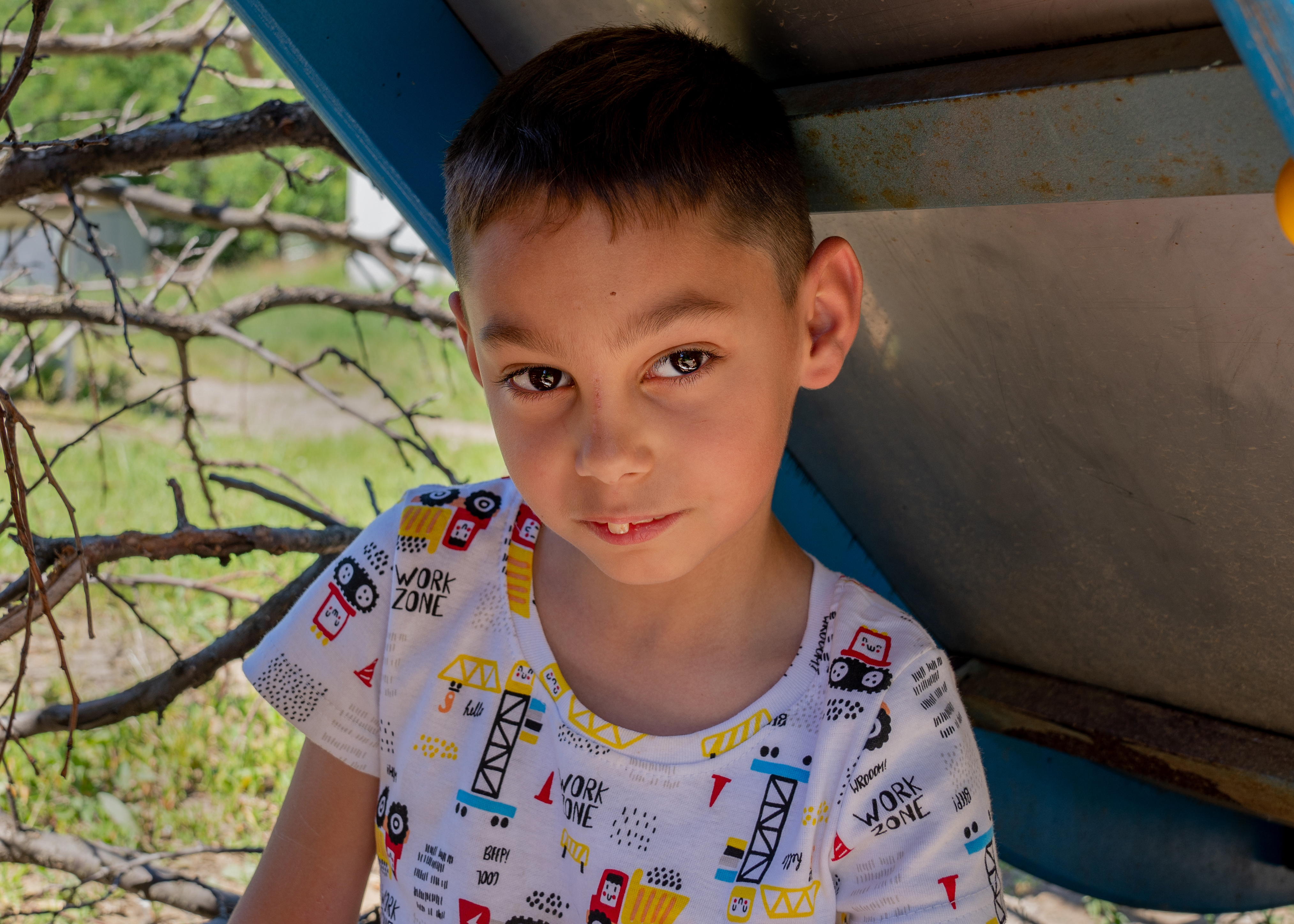

Two brothers on their first day after crossing the border from Ukraine to Romania.

Evacuation From The East

5 am, Andrei writes on his daughter's back, in case she gets lost. In black marker, emergency phone numbers and names. His son Andrusha waits for his turn. Then he drives his family from East to West across Ukraine to a safer part. To then leave them and go back to volunteer.

A stop during an evacuation from Bahmut. A woman runs to the forest to use the bathroom. I worry about landmines and keep watch.

During the evacuation from Bahmut, approximately 500 people assembled, but we only had the capacity to transport about 100. My heart breaks, as elder women cry to me, saying please take us too. I tell them we’ll be back. Children and woman are seated first. It feels surreal, like a scene from The Titanic.

Evacuating elderly individuals with disabilities from Eastern Ukraine, using mattresses laid out in a van.

Kramatorsk train station, captured a week before the horrific missile strike that resulted in 63 civilian deaths and injured 150 others. People spend days waiting for a chance to board a train heading west.

The elderly placed in temporary transition housing, utilizing spaces like church buildings and schools. Amidst uncertainty, many are unsure about their next steps - where to go from here or what to do next.

Families who, against all odds and amidst severe challenges, managed to escape from Izyum, a city that was under Russian occupation for several months. With 80% of the city devastated by Russian bombings, many were unable to flee. Most of the escapees I encountered were reluctant to discuss the tragic events. The younger children continued to play, not fully comprehending the situation, while the older kids were more aware of the grim reality.

Article & Photography published in Progressive Magazine:

On the Line: After the Bombs Fell, a Ukrainian Village Rebuilds

On the Line: After the Bombs Fell, a Ukrainian Village Rebuilds

Petya and Natasha, who had a baby right before the war began, returned to find their home gone. Now they live with their infant son David in a small chicken coop next to where the house once stood.

Lydia says she found Russian packets of food on her kitchen table. She wiped them down about twenty times, she adds, but they still feel dirty. We sat at the table and drank instant coffee while she told me how her dog Maxwell went missing when the shelling began, and didn’t turn up until forty days later when the village, Moschun was liberated. By then, his hair had turned gray from the stress. Her house has a massive hole where it took a missile hit, and the roof was destroyed. A photo of her great grandparents still hangs on the wall.

Lydia’s neighbor Tanya’s home was also destroyed; the windows were blown out, parts of the ceiling were on the floor, and there’s a bullet hole in her television, while Jesus and Mary remain upright. It’s not too bad, she says. At least the walls are still up.

Lydia showed me where another neighbor, an older woman who lived alone and was killed in the attack, was temporarily buried. Ukrainian soldiers took a sheet from Lydia’s house and wrapped the body in it. They made a cross out of two sticks, and laid her in the soil by the forest. Together, we visited the grave as Lydia explained that, although they’ve reburied her since, they left the sheet and makeshift cross in the spot where she had first been placed.

I met another woman, Victoria, while I was talking to a local shopkeeper who had lost her home and business. Victoria and her husband Volodymyr stayed in the village during the Russian occupation. We went to her home for soup, where she said the reason they stayed was because they couldn’t leave their livestock—goats, chickens, cats, and dogs—to starve or be eaten by the Russians.

During the heavy bombing, Victoria would hide in a small, rectangular metal box, where the couple once kept their valuables. She crouched in a fetal position to fit in the box as her husband kept watch, many times for hours.

During the heavy bombing, Victoria would hide in a small, rectangular metal box, where the couple once kept their valuables. She crouched in a fetal position to fit in the box as her husband kept watch, many times for hours.

Another Moschun local, a woman in her eighties who goes by Baba or “Grandmother” Lida, also stayed behind. During the shelling, she put out house fires all around her with buckets of water from her well. Her hearing has gone bad after hearing the bombing for 40 days.

The government and volunteers give out groceries—grain, oil, eggs, and canned food—once a week on Saturdays. The line can take up to two hours, and recipients must prove they are residents of that particular village.

There were no strategic military targets or bases in Moschun, just people’s homes. White phosphorus bombs, illegal to use near civilians, were dropped here. You can see their impact as you walk around the village; nothing is left where these bombs exploded.

Lots of pets have been left behind amidst the turmoil. Some loyally linger near their demolished homes, while others roam without direction. I feed any I come across, using the pet food I carry in my backpack.

I met a woman named Luba, her son Sasha was killed right in front of her at the gate to their house. A shell struck him when he was trying to evacuate her and other residents. Pieces of him flew, and all they found whole was part of his leg. Luba said she was afraid to come back to the village once it was freed from Russians. When she did, she found her house gone as well. Her neighbor also lost their house, a young mom with three little kids. Now that Luba’s back, she says she can’t imagine not being here, she feels her son here. And this is her home even if it’s completely destroyed. She showed me the vegetable garden she planted, the progress on cleaning the yard and the hole where the shell hit Sasha, already covered with sand. When Luba came back she dug up what was left of her son and buried him a second time. This time the proper way, in a cemetery with a ceremony.

Landmines surround the village. I am repeatedly warned to avoid wandering through the forest and near houses marked with the spray-painted word "Landmines." For safety, using the bathroom is limited to areas that have been confirmed as cleared. Lydia advises me to use her bushes for this purpose, as she has been doing so herself due to the lack of functioning water and electricity.

In the face of this massive destruction, few aspects of village life have remained unchanged. However, villagers have continued to tend to their fruit and vegetable gardens. No matter what state their house is in, the gardens are in neat rows, ready to harvest when fall comes.

Kharkiv - Living Under Daily Bombing

In Kharkiv, numerous individuals, including children and pets, have taken refuge in the metro, seeking shelter from the daily bombings. Volunteers have installed bunk beds to accommodate the needs of those taking shelter. Everyone is waiting for the war to end.

The city has an eerie and heavy atmosphere, yet life continues. In Saltivka, Europe's largest residential neighborhood, which endured intense shelling daily, people have started to return despite the area still being bombarded daily. Utilities like power, water, and heat are non-functional. Residents are seen clearing broken glass and debris, and collecting water from damaged water stations. No shops are operational. Occasionally, volunteers distribute hot food in some areas. Most people who have return are either poor, elderly, or have nowhere else to go.

Borodianka, Irpin, Bucha (Kyiv Region)

A boy in Borodianka stands where his room used to be. He finds a piece of his toy and looks at it.

A grandmother and her granddaughter display weapon fragments found in their yard, remnants of the attacks in Irpin.

Borodianka is the most destroyed city in the Kyiv region. Everywhere you look, you see the war crimes.

Grandma Olya remained in Borodianka when most residents fled. The attacks resulted in approximately 200 deaths. She recounts how Russian soldiers entered her home, looting possessions and interrogating her and her husband. Despite the danger, she insisted they were just an elderly couple with no information to offer. Amidst the bombings, she would crawl to her shed and the abandoned shed of her neighbors to feed the animals. Together with other volunteers, we repaired the broken windows in her house to prepare for the cold winter ahead.

Fresh graves being dug at the cemetery in Irpin for all the deaths by the Russian attacks. A stray dog, having survived the bombings and assaults, lies beside them.

"Molotov Cocktail" and a car riddled with bullet holes has "F**k the Russians" spray-painted on it.

People gather in church to pray for the war to end.

The land I love. The land where I lived. Where I grew up. Where I studied. Where I worked. Where I loved. Where I felt, heard, saw, smelt and tasted all around. Where part of me remained and a part of me left.

Is it pure luck that some lived and others died? The right place at the right time. The wrong place at the wrong time and then a bomb, a missile, a drone.

Pain streaked across faces. No certainty. Fate given to chance. Missing the way things were. Life uprooted to start over again. Despite the death, decay, destruction, despair, all the D words. Waiting to go back to the land they love.

I’ve felt the spectrum of emotions: injustice, fear, rage, grief, pain, hope, joy, disappointment, relief and then all over again. A whirlwind.

But hope lives on. A hope that Ukraine will win this war, rebuild and live in freedom.

Is it pure luck that some lived and others died? The right place at the right time. The wrong place at the wrong time and then a bomb, a missile, a drone.

Pain streaked across faces. No certainty. Fate given to chance. Missing the way things were. Life uprooted to start over again. Despite the death, decay, destruction, despair, all the D words. Waiting to go back to the land they love.

I’ve felt the spectrum of emotions: injustice, fear, rage, grief, pain, hope, joy, disappointment, relief and then all over again. A whirlwind.

But hope lives on. A hope that Ukraine will win this war, rebuild and live in freedom.